- Home

- Sara Dahmen

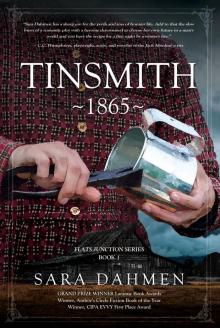

Tinsmith 1865

Tinsmith 1865 Read online

TINSMITH 1865

Copyright ©2019 by Sara Dahmen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without prior written permission. This is a work of fiction. The characters, incidents and dialogue are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. Care has been taken in properly representing the names and language of the Sioux, but the beautiful words cannot always be perfectly represented, and the author asks forgiveness from the original caretakers of the Plains, and continues to study Lakȟótiyapi every week to better understand and speak it.

Promontory Press

www.promontorypress.com

ISBN: 9781773740423

Cover designed by Edge of Water Design

Interior Artwork Copyright © 2019 Sara Dahmen

To Bob, Marilyn, and all the tin tinkers, and my husband, who understands how the stories burn and glow and gives me the time to write them.

14 August 1853

To my Friend Wladisław Salomon,

Greetings. Jozefa and I received your Letter when you wrote of your impending Journey west from Philadelphia. I hope you have arrived in Safety and you will write when you can of your Life.

We are settled in Chicago as we were when I last wrote. Jozefa has found many Friends with the Polish here and the Children are growing well, as is the Business, though I envy your continuing Adventures. Jozefa does as well. She sends her Regards to Monika.

In Friendship,

Stanley Kotlarczyk

Chicago

06 November 1862

To my Friend and fellow Smith, Stanisław Kotlarczyk of Chicago, Greetings from the Dakota Territory.

I have asked my Friend, Harry Turner, the Owner of the Mercantile here, to write this for me.

We departed Independence for the Dakota Territory in Spring. I have a Smithy in Flats Town, which is Well-Placed on the new Wagon Trail. With the Homestead Act, we now have some Land, though I do not know how to Farm. The Territory is growing each Year. You might Wish to come West with your Family soon.

Monika sends her Regards to Jozefa.

Yours in Faith, and in Friendship,

Wladisław Salomon

W

18 December 1863

To my Friend Wladisław Salomon,

Greetings. We have received your Letters, and considered Plans to join your Family. However, my Sons are off to War, and we Dare not leave Chicago until they are Returned to us. I do not know when or how we will get to Flats Town.

In Truth, we are very Distraught by this War, and with two Boys fighting, I know Jozefa worries that our Wojciech will need to Enlist in time. You are Fortunate you will not need to send your Children to Battle.

In Friendship,

Stanley Kotlarczyk

Chicago

12 November 1864

To my Friend and fellow Smith, Stanisław Kotlarczyk of Chicago, Greetings from the Dakota Territory.

I have asked my Neighbor, Joe Greenman, a Good Man, to write this for me. We are growing quickly here in Flats Town, as Fort Randall to the West continues to be Important and Yankton is booming, especially as it is the Capital of the Territory. There is Much Need for more than the occasional Tinker that comes around every other Summer, and you and your Sons would find enough Work to keep all four of you busy should you come West.

The Wagon trails go through here to stop in a traditional place at the old buffalo jump, and there are new Arrivals often. They are building a Railroad in the East, which we are sure will run through Vermillion next, then Yankton and then Flats Town. Our Banker says we will then rename the place Flats Junction. You will find the rail will Bring more Work and materials will Arrive quickly. Perhaps buy a New Machine if you can Afford it. The Novelty will draw customers Quickly, and I will Advertise of your Skill before you arrive. Send Word of your decision so I might Prepare for you.

Do not Speak of this to Jozefa, but know there are small Battles still Fought on the Plains between the Army and the Natives. While none have been in Flats Town lately, it is the Wagons they will sometimes Target. There is Danger in coming, but the Rewards for life here are far Greater than you would Imagine.

Yours in Faith, and in Friendship,

Wladisław Salomon

W

18 January 1865

To my Friend Wladisław Salomon,

We will come to Flats Town as soon as Tomasz and Ludwik return from the War. Jozefa and I are Agreed. If you might secure a Building for us, we hope to come out in the Spring.

I will make Inquiries about the Travel and a Wagon. Jozefa is glad to know there are Polish where we go, and we hope there is a Church as well. The City is growing fast, and there are more Craftsmen every Month. We will be glad for the Work in the West.

My son Tomasz will bring his Bride out if the Marriage can be made in time. Look for us in the Spring.

In Friendship,

Stanley Kotlarczyk

Chicago

8 March 1864

To my Friend and fellow Smith, Stanisław Kotlarczyk of Chicago, Greetings from the Dakota Territory.

I have asked Father Jonathon, a Good Man, to write this for me. He is the Priest in Flats Town. You may tell Jozefa.

A Building is secured for your Family. It is not much. A Barn on my Property I can Provide. It will take much Work to make it a Home and a Shop, but with your Sons to Help, I am sure it will Suffice. Please tell Jozefa I Apologize I cannot offer More.

Be Well and Safe on your Travels. I will watch for you in the coming Months.

Yours in Faith, and in Friendship,

Wladisław Salomon

W

Wagon Road

DAKOTA TERRITORY

30 June 1865

CHAPTER ONE

30 June 1865

The dust rolls inside my skirt. It feeds the layer sifting to the bottom of my stockings and digs itself into the cracks of my heels. I can smell it, breathe it, taste it. It has no color until it gathers in the creases of my neck. Then it is a chalky black, though the sand and land around me are dun and red and tan.

We’re rounding up early today. The head of the wagon train curves back around toward us at the rear, snaky and wobbling as the oxen lumber and low, and the horses scatter.

“You better get back there and get ready for supper,” Tom mentions, jerking a fat thumb behind us into the stifling shade of the wagon’s box, and stretching a stiff leg over the top of the seat. “See if you can manage dinner decently tonight.”

“It’s not like there’s much I can make,” I retort. “Flour, beans, rice, and root vegetables.”

“For once you might figure out how to put all those things together and make something taste like real food, so.”

“‘Real’ food?”

“It can’t be as hard as you make it out to be, Marie,” he complains. “Mother always—”

“Shut up.”

I don’t need another reminder of Mother. And why does Tom need to mention her anyway? It’s not like he was there at the end.

“Well, get back, so,” he says again. “Or Father and Al will be griping worse than me.”

Clambering over the seat and under the rain-stained canvas, I wince as I climb around the trunks, and hit my shin on one of Father’s boxes.

“Damn!”

“I heard that!” Tom calls through the flap, his shadow hazy and grey against the soiled fabric. The wagon churns below me. The thin wood has warped along one side, grinding and smashing against the iron band of the wheel on the right as he swerves the bull team to match the others in a rough circle.

“Well, damn anyway. It hurt,” I say quietly, rubbing my shin

on the small box holding the treasured burring machine. Tom must not hear me the second time, or else he’s concentrating and doesn’t care. I glance down, and suck in my lips. The new tinsmithing machine is a heavy lump snuggled in a revered pad of cotton wadding and rags. I’ve wanted to turn the gearbox once, just to do it. To prove I can. There’s no chance any of my two brothers, or Father, will let me touch such a beautiful, gleaming, efficient wonder, but if I’m quick enough, I can take a peek before I need to jump out and start unloading the camp kitchen for dinner.

They won’t see what I’m doing. Tom’s busy with the oxen, and Father will be guiding one as well to help. And heaven knows where Al is at, walking somewhere behind us. It’s now or never.

I unwind the fabric, noting the black stains of slippery grease on it, and feel under the edge of the blankets for the base of the machine. My fingers shake. I’m petrified I will drop and break it, rendering it useless and my father’s investment lost. It was incredibly expensive—almost eight dollars—and with it is our future.

Opening up the rest of the sack, the round wheels and choppy gears of the metal are revealed, and I reverently lift up the burring machine so I can settle it onto my lap. My apron is already stained with food and grime, so the extra grease does not make much difference. I tuck the short, fat, stake end into my thighs, and hold on tight as the wagon lurches again. Running my fingers along the perfectly cut iron, turning the crank, and watching the round plates slip and slide past one another, I sigh. It’s beautiful. I’m no trained artisan by any means, but I can understand the wealth and hope tied up with such a thing.

Pinching up the fabric in the box open, I heft the machinery in one palm, the comforting weight of the iron matching the strength of my wrist, just as the wagon box pops up once more and the slippery oil on my fingers gives way. With a fat, deadening thump, the burring machine smacks the brass edge of the trunk at my hip, pounding onto the iron stake plate nestled between the boxes, and smashing into my foot.

“Pieprzyć go! Fuck it!”

“What are you swearing at in there!?” Tom bangs on the edge of the wagon from the outside, and I yank up straight, my heart pounding, my breathing coming fast and hard, and the heat of the wagon receding into a quiver of chills.

Please don’t let it be broken … Prosić … please …

“Marie?”

“Dropped a … box!” I call out, hoping my surly older brother doesn’t think to poke his head in just yet. He can’t. He …

I pick up the machine and turn it over in my hands. A pebbling tremble runs down my fingers, my heart drops, and my mouth cottons. The slender wrought handle, which should crank the disks together, is bent inward, the curl of it gouged from the stake plate, and the threads pulled halfway out of the socket.

My God! What have I done?

I cannot take another breath without the panic breaking loose, and the strange chill sprints up my arms, matched by the thin river of sweat burrowing along the blades of my shoulders, and down the crease between my breasts.

The wagon slows, and Tom stands. Al’s voice mingles with Father’s, and without another thought, I tunnel the burring machine deep into its packing. Worry splits my head, shame and disappointment in my own clumsiness worming into my chest.

“Marie, you making food?” Al yells in, the canvas dampening his shout.

“I am!”

I shuffle toward the camp kitchen box, letting the shake of my hands flicker through me as I start taking out the big skillet and pot, my mind skittering over the lines of the machine. It was supposed to make the journey to Dakota Territory without issue, but I’ve destroyed it.

Is it an omen? Will we be shattered during the thirty-day journey to Flats Town too? Or is it a sign of what’s to come once we reach the end of our trip?

Pressing my lips tighter together, I sort through the box of turnips and try to pretend that I haven’t touched the damn machine at all.

CHAPTER TWO

3 July 1865

“Oh, damn! Not again!”

I stare at the stew. The bubbling broth is thick with ever-available flour, but I’ve forgotten to add rice.

“Ha! Ruined soup and a curse, too, sister?”

I swat my oldest brother as he walks by, surveying the scene and shaking his head.

“Don’t torment. I’ll have it fixed in a moment, just see if I don’t.”

“Pah. You always say so.” He keeps teasing, grabbing a crust of hard bread off the makeshift sideboard.

“I’m right at least half the time,” I press, and he laughs with a mouth full, walking over to the fire to poke it with the iron. “Tom, I’m not such a bad cook.”

“You’re not, Marie, really,” he obliges with heavy sarcasm, and then stuffs the rest of the crust into his jaw, gnawing and smacking his teeth together.

Father comes around the corner of our wagon, carrying a small bag.

“Trading a tin box for some onions,” he says proudly, his Polish accent heavy and thick on hard-won and imperfect English.

“Who has onions?” I wonder.

“Cooley’s.”

Tom frowns. “Pfft. We have stores of vittles enough,” he reminds Father. “Why go wasting good made tinware for some vegetables?”

Without pausing, Father bends down and opens the burlap. Round, globular, onions cascade out of the sack, breaking their translucent skins as they tumble onto the packed dirt of the prairie. I catch one up and inhale the pungent flesh. The first thing I think about is how well they will be to make a soup I likely won’t ruin.

“I’ll add one to the stew,” I announce, and am rewarded with Father’s brilliant grin.

“Ha! Do you even know how?” Tom asks.

I push away my irritation, and answer as calmly as I might. “Even if I didn’t, I’ll figure it out.” I sound defiant anyway. He shrugs it off.

“Well, that’s something, then.” Tom sighs and disappears behind the wheel spokes. Undoubtedly he’ll re-count our stores of goods in his head as reassurance as he goes to check over the wagon. We’d bought the lighter prairie schooner for our month-long journey at the railhead in Marshalltown, Iowa, but it was quickly made and needs repairs nearly every night.

Turning back to the blackened pot, I make quick work of the biggest onion on a nearby rock, and add the savory spongy bits to the stew. Father watches me the entire time, and when I finish, he smiles again. It has been long since Father has smiled so much.

“You do that deftly as your mother did,” he mentions, and the compliment makes my fire-ripened cheeks flush further. “The saving of a soup. She could always save a soup …” The memories choke him, and he falls silent. After a moment, he walks away toward the deepening shadows of the wagon circle. I press my lips together and turn toward the onions. At least the cutting of them will give my misty eyes their own excuse.

While stirring the different pots and skillets, churning the rice, I glance at the hardening vegetation around us. We flatten the prairie grasses quickly with our encampments. The ocean of grass, and the smudge of trees on the horizon dips and flows, while the feathering road stretches westward where others have already traveled. The clumsy wagons create a shield against the emptiness of the plains, and the flaps of linen against the frames are tempered by the noise of two hundred bodies preparing to eat. There are many of us, and we leave a trail of graves, black campfires, and garbage every night we make a circle.

I wave tentatively to Agatha Cooley, who usually camps next to our wagon. She grins at me, and I try to match her enthusiasm, but the truth of it is I am too choked with worry about the machine I’ve broken and the terror twisting through me each night on the prairie.

The tension always mounts as we settle in for the evenings. Will the night be peaceful? Will we wake with a camp full of corpses? Illness? Fire? Will a troupe of angry Indians find us? Have they been trailing us? The litany of questions is unstoppable. Even with the peace the government promises, horrifying stories trip and ripple

around campsites on their own accord.

The smoke billows around my skirts, black and brown, and yet finally smelling like something resembling edible food. Would Mother be proud I’ve salvaged it? Would she be giggling with Agatha Cooley and still pull off a delicious meal? Likely. How I wish she were here!

I rock back on my haunches, and finger the grease stains on my apron, wondering what would have happened had we stayed at the railhead in Marshalltown after riding the train from Chicago. Suppose we had never started this meander through the undulating grass and bluebell sky. Would I marry? Would we find work?

Nearby, the older Cooley children start to chant one of the walking songs from earlier in the day:

With a merry little jog and a gay little song,

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy,

We trudge our way the whole day long,

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy.

What though we’re covered all over with dust,

It is better than staying back home to rust,

We’ll reach Salt Lake some day or bust!

Whoa! Ha! Buck and Jerry boy.

I do not hear my brother Albert come up, but suddenly he appears on the opposite side of our campfire, his eyes glittering with energy.

“And where have you been? Certainly not helping around here!” I sputter, feeling disconcerted to have my mulling snapped.

“Making the rounds, as always,” he says calmly, and takes off his hat. The line of the brim glows. Both of my brothers have a deep crease along their foreheads, where dust and reddened skin meet a gash and then a sallow swathe of virgin flesh before touching their scalp. Al’s hair is burnished and tarnished gold in the campfire glow. Above us the early stars pulse and rotate with blue-white gleams. Everything feels bright and stark on the prairie. Will it be the same in Flats Town?

“Anything worth noting around camp tonight?” I ask.

“Naw, not tonight. So, let me help you now, siostra,” Al offers, reaching to grab the spoons and knives. The onions in the skillet are a mix of clear and opaque, their shimmering whiteness sparkling against the patina of the blackened cast iron. They look ready. I add them to the stew, and hope it’ll pass the stomachs of my menfolk.

Tinsmith 1865

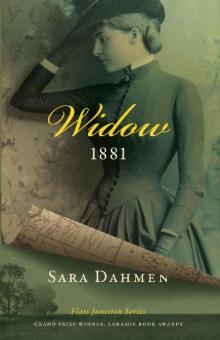

Tinsmith 1865 Widow 1881_Flats Junction Series

Widow 1881_Flats Junction Series